Parliaments are legislative assemblies, though they often have different names (Congress, Althing, Cortes, Duma, Diet, Riksdag, Sejm, etc.). Despite some similarities to the Roman Senate, modern parliaments developed from European traditions begun in the Middle Ages. Some parliaments, including the British Parliament and the Icelandic Althing, have survived since that time. Other parliaments, such as the U.S. Congress and the Japanese Diet, are based on European traditions.

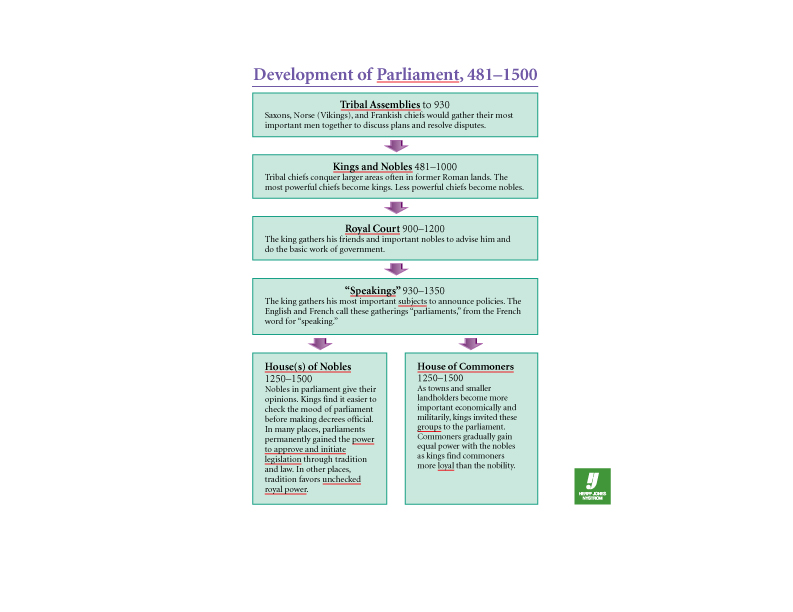

Roman writers observed the tribal assemblies in Germanic and Celtic tribes outside the Roman Empire, long after the Roman Senate had lost its power.

The Germanic tribal assemblies were called dings (also ling, thing, or ting depending on the region). These assemblies continued as the Germanic tribes expanded into the Roman Empire. The local dings remained especially strong among the Norse and areas with strong Norse influence including the British Isles, Poland, and Kievan Rus.

The Germanic tribal assemblies were called dings (also ling, thing, or ting depending on the region). These assemblies continued as the Germanic tribes expanded into the Roman Empire. The local dings remained especially strong among the Norse and areas with strong Norse influence including the British Isles, Poland, and Kievan Rus.

Tribal assemblies usually elected their chiefs. However, as chiefs became more familiar with late-Roman and Christian traditions, they imitated those traditions including hereditary rule. The Church, hoping to reduce disorder, recognized these chiefs and gave them their official blessing, which also helped gain the loyalty of the local (often Roman) population.

The royal court tried to carry out the king's plans, advised the king on potential plans, and settled disputes among his subjects. The court grew to include more nobles and clergy, giving the king a broader set of views and providing a means of watching potential enemies. Eventually the functions of the royal court would be divided into the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government.

The Althing of Iceland was created in 930 and is the oldest continuously operating parliament in the world. Most countries in Europe established some type of parliament during this period. Not all of these assemblies survived to the present day.

The most important subjects were the high nobility, who owned huge amounts of land and commanded many knights, and the most powerful bishops and monks, who also owned huge amounts of land, controlled the only educated people in the kingdom, and often had the most popular support.

The nobility and clergy would eventually form one (England's House of Lords) or two (the First and Second Estates of France) houses in the developing legislature.

The nobility and clergy would eventually form one (England's House of Lords) or two (the First and Second Estates of France) houses in the developing legislature.

Conflict between the king, the nobility, and the clergy had gone on before the development of parliaments. Parliaments continued these conflicts but provided a means of settling them as well.

Kings dealt with the conflicts differently. Some consulted with the parliaments, making sure parliament accepted the royal policies. Others stopped calling national parliaments, keeping the nobility divided.

Kings sought to check the growing influence of parliament over national affairs. Parliaments hoped to protect their power. As a result, new laws and procedures developed that defined the powers of parliaments, how often they would be called, and eventually protected members from royal retaliation. These areas developed into constitutional monarchies.

In some places, traditions allowed the king and his ministers to rule without consulting a national parliament. Appointed officials would hold most of the real power with regional parliaments called only to inform the local leaders of new royal policies. These areas developed into absolute monarchies.

Increasing trade and industry made towns more and more important. Kings granted charters to these towns, placing them directly under their rule and free from the control of the nobility. Cities and smaller landowners were invited to send people to parliament. In France this would become the Third Estate; in England it would become the House of Commons.

Cities were ruled by appointed royal mayors working with a city council, usually made up of guild masters. The city council or the city electors (wealthy city residents) chose the people to represent them in parliament.

The nobility often included people who wanted to be king. Commoners, on the other hand, did not have such ambitions; as a result, they did not usually plot against the king. Also the economic interests of the commons in parliament (usually wealthy merchants and lawyers) were tied to peaceful order and their royal charters.